The Secret To Divorce Success: Retool Your Resilience

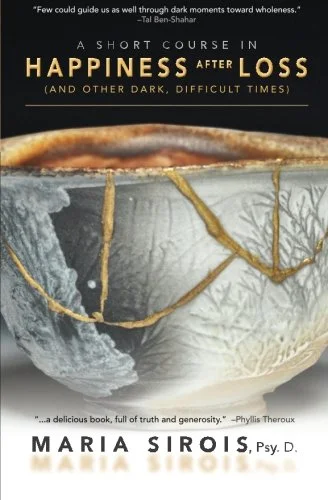

/Maria Sirois is the author of the recently-published book A Short Course in Happiness After Loss (Green Fire Press, 2016). The book combines the science of positive psychology with research on resilience to offer a “curriculum” for feeling stronger during hardship. It's also a guide for reconnecting to our sense of meaning. Sirois is a licensed clinical psychologist who teaches at the Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health in Massachusetts and works as an inspirational speaker and consultant. Her book takes the position that both resilience and happiness are choices we can make, even during tough times.

I was excited to talk to Sirois about how her work applies to those of us facing divorce.

Wendy Paris: I love the idea that we can choose to become more resilient and even happier, but aren’t resilience and even optimism inborn traits—you have them or you don’t?

Maria Sirois: We know that there is some “genetic loading” for positivity, happiness and resilience. You can have DNA that leads you toward pessimism and anxiety or toward optimism and happiness. Some of us have a neurochemistry that works in our favor toward resilience or against it.

But the research points to the fact that there is much more flexibility than we realized. In the 1980s, we thought you were lucky enough to be resilient or not. But it turns out that’s not true.

The tools and practices of positive psychology can be learned at any age and they stir resilience. These practices have a huge impact on your neurochemistry, your heart, your health, and also your sense of agency. Feeling more resilient makes you act more resilient. It’s a beautiful “virtuous cycle.”

Wendy Paris: So how do people become more resilient?

MS: Resilient people make conscious choices every day to put aside time for practices that energize them, enliven them or strengthen them—that build their capacity, strength, perseverance or endurance. The key is that they make the conscious choice to do so. Research shows that prioritizing those things that lift or strengthen you builds resilience. These choices literally change our neurochemistry. Some people seem to have been raised in ways that inculcate this, or they have a natural capacity to do this. Many of us, however, have to learn that this is what we need to do.

The “beautiful” opportunity in divorce, is that because things have fallen apart, we have a rich opportunity to really live our lives differently, and we do that by living our days differently.

You have to ask yourself, “What are the things I know that actually lift me? That make me feel good about being alive?” Is it music, yoga, mindfulness practices? Where can you go to engage in those activities?

Wendy Paris: I think a lot of people have trouble remembering what makes them feel good or gives them energy. How can people get in touch with the things that give them strength after leaving a stultifying or conflictual marriage?

MS: This can really be hard for people if they’re not in the habit. Not asking also makes it hard to notice the small things we love. Also, who you are today is different than who you were in the past. What most lifts or builds you may not be the same thing that worked years ago. Just taking time to ask yourself the question is a start.

The powerful overarching teaching of asking yourself what you love, on a daily basis, is that you’re teaching yourself two important things. One is that you care about yourself. And the other is that every day matters. Both of those build optimism and energy. People say to themselves, “I don’t know what I love.” And then they try volunteering or going to the gym, and it doesn’t work for them. They feel like they’ve failed and they give up. But they don’t realize that the discipline of asking themselves is invaluable. You need to give yourself time to come up with the answers. They won’t come right away if we’re not in the habit of considering ourselves.

There are two ways to figure out what lifts you:

1. Make time for mindfulness.

A mindfulness practice really helps you identify what you love. Set aside a few minutes every day for stillness and reflection; once you’re still, you can sit quietly and ask yourself what you love. Do the mindfulness practice for five to 10 minutes, and then ask yourself that question.

2. Write down your thoughts.

The second technique that’s helpful for people dealing with divorce is daily journaling. Sometimes when we get divorced, we realize that we’ve been doing some things because of the obligations of the couple or the family, but they don’t really nourish us. You can write your journal at night or in the morning. At night, you might ask, “What excited, energized and lifted me today?” Or you can do it forward-looking, and ask yourself, “What am I excited about this week?” This helps you get clear about who you are at this stage in your life.

There are so many disruptions to your identity and to your way of living after divorce, or after any kind of loss. The old normal doesn’t exist anymore. But we’re not in the new normal yet. The transition time can be confusing. There can be an untangling of what had been part of the marriage and what is you. All of this takes time.

Wendy Paris: You talked a little about what helped you in your divorce. Can you elaborate? Did you use your own techniques?

MS: I had a journal when I got divorced. I wrote down my answers to the question, “What do I love now?” It helped me start noticing what made me exited. I still love going to rock concerts, for example. I’m 55, and I still love Bon Jovi. I’m no longer excited volunteering for charitable organizations, being on their boards. I still do a tremendous amount of charitable work, but I don’t want to sit on boards, probably because I spent a tremendous amount of time in my 30s doing that.

One of the things that came out of my divorce was that I kept hearing myself say, “I just want to love what I love!” If I love blueberries for breakfast, I’m eating blueberries. If I love the idea of going to Dublin, I’m going to Dublin. It’s this notion of doing what I love and building it into my schedule.

I love to dance, but we don’t really have clubs here where I live, or the ones we have are a lot of 20-year-olds, and that doesn’t make me feel good. I’m at the stage where I don’t have a lot of weddings to go to, so I’m not dancing there. My love for dancing has been translated to going to concerts, just being around music. The search for music performance has been something I’m prioritizing.

Resilience gets built through the acts of resilience. You can’t just think your way into a happier life or a resilient life. We are at our best, even in difficult times, when we build in the chance, each day, to experience something that we love, something that builds self-esteem, or a sense of our own competency.

The important point of all this is that we do want to do things that truly lift us, not the things we think we should do. One of the things we know is that being true to ourselves lifts resilience.

It makes you a little quirky, being true to yourself. We’re not all the same. I love wearing yoga clothes. I don’t do yoga, but I love wearing yoga clothes. Enjoying the things that are a little quirky about you is also energizing and strengthening.

Wendy Paris: Okay, I have the problem of some self-judgment about what I love. Like, maybe I’m being lazy here, wearing yoga clothes and flats. Or, I’ll stay home and cook dinner with my son, and feel like I should be out meeting new people. It’s really hard to know what’s being true to your “quirky” self, and what’s just listing into comfort because it’s easier.

MS: We all have certain judgments. I didn’t date for two-and-a-half years after I divorced. I had a lot of judgment around that. “You’re isolating yourself. You’ve created this tremendous opportunity, by getting divorced, but you’re not taking advantage of it.” I’d be reading in bed on a Friday night, and feel bad about it because I wasn’t going out.

The principle I leaned on was the principle of the “AND,” which is a tenant of positive psychology. Rather than thinking, “If I wear heels and dress up, there’s something more worthy about me than if I wear flats and cook at home for my son.”

The “and” is where we give ourselves permission to be fluid and flexible, not so black and white.

The principle of the “and” is that you say to yourself, “I need to be home on Friday night and rest, and I also give myself permission to go out. I can be a good mother cooking at home and I can be a good mother when I’m filling myself with energy by going dancing.” Start living into more flexible ways of seeing and honoring ourselves.

Self-judgment doesn’t build resilience or happiness. It just doesn’t. It leads to depression and anxiety and low self-esteem.

As we’re trying to figure out what our new, healthy normal looks like—which takes years, by the way—we want to give ourselves as much permission as possible to do what is healthy for us. Some nights, healthy and self-caring is staying home. Some nights healthy and self-caring is being ambitious and going out. Divorce can kick up all those underlying self-judgments we tend to have carried with us since childhood, and it's also the perfect time to begin to let go of them. There is no one right way to live a thriving life. There are a thousand ways!

Wendy Paris: That's helpful. Thank you. One last question: How do we make time for the activities that build us up?

MS: You have to put it in your date book. Say you want to start yoga. Write down, “Go visit the yoga center tomorrow.” Or “Find the coffee shop in your new neighborhood.” You have to prioritize it. Resilient people shape every day. It becomes not like work, but more like an experiment. Try to wake up and say, “What’s the thing I can do today that energizes me? Well, I know that exercise energizes me. So I’ll try to exercise five times this week and see what happens.”

After my divorce, I wanted to try new forms of exercise. I bought myself a bike. I joined a bike club. Then I got a bike instructor because I didn’t know how to shift gears. Then I started being brave about reaching out to people I know who had road bikes and saying, “Would you mind going out on the baby hills with me?” I wrote this all down in my day planner. It’s a daily choosing; even just 10 minutes of something that lifts you will strengthen you and build resilience.

These practices really change our brain chemistry. I’ve been exercising for 40 years. If I stopped for three months after doing it for years, I wouldn’t actually go back to my brain chemistry of 40 years ago. Much of that positive learning has been solidified. New habits, however, take time to take root.

The best approach we can take is to consider each day as if it matters, shape it, even just a little bit so that it works to lift us, and practice this approach each day.

Over time, this new way of being takes hold in our minds, our hearts, and in how we see ourselves living our lives.

Wendy Paris: Thank you. This is great!

***

Wendy Paris is the author of Splitopia: Dispatches from Today's Good Divorce and How to Part Well (Simon & Schuster/Atria, 2016). Splitopia and her work on divorce have been covered by The New York Times, Real Simple, The Washington Post, The New York Post, The Globe & Mail, Psychology Today, The Houston Chronicle, Salon.com, Parents.com, Family Law Quarterly, PsychCentral.com and radio and TV shows nationwide. She has an MFA in creative nonfiction writing from Columbia University, and is an advocate for family law reform. She is divorced, and lives in Santa Monica, California, a few blocks from her former husband, with whom she has a warm co-parenting relationship.